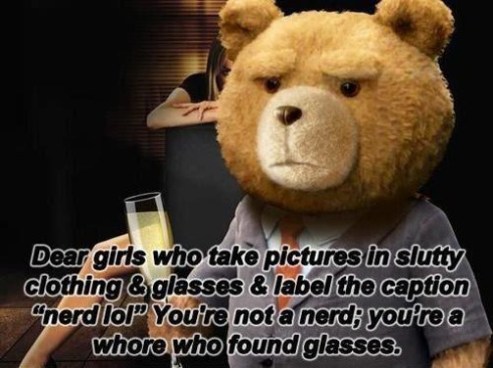

Marie-Pierre Renaud’s 5-part article in The Geek Anthropologist argues that stereotyping women with a ‘nerdy’ interest as not real nerds, and instead as shallow girls who happened to invest in a pair of large glasses, is unfair. The amount of antipathy towards ‘fake’ gamergirls that she references is honestly appalling. For example, a comic book artist shared the below image on his facebook page to his followers:

The assumed-fictitious geeky interests of gamergirls is attacked by attacking their sexuality. If the situation were reversed and a man had an interest atypical of his performed gender, I don’t think he would be belittled in the same way. He may experience judgment, but I don’t think they would be as focused on his vapidness or sexual promiscuity. Later in her article, Renaud reviews online rants made by individuals angered by ‘fake’ gamergirls. These rants centered around two basic problems. Firstly, they seemed to think that women who pretend to have an interest in geekery only do so to attract male attention. Secondly, they assume that this display is not based in any nerdy knowledge and that their existence detracted from the value of actual geek culture. Two of the three ranters also expressed resentment based on the idea that fake gamergirls would pay real nerds any attention outside of conventions. In an attempt to rationalize this rejection, these ranters came to the conclusion that attractive ‘fake’ gamergirls were fake and stupid. Cue eyeroll. While Renaud ends her article by stating that each of the ranters also recognized the ‘true’ gamergirls, the adjectives associated with them were humility, and non-attention seeking. This seems to be a microcosm for the gender roles given to women in our society at large. The Virgin vs. Whore stereotype pigeonholes women into one of two categories, but gamergirls (like the rest of us) are not fully defined by two contrasting, problematic, categories.

(http://thegeekanthropologist.com/2014/03/31/the-fake-geek-girl-project-2/)